This Faculty Focus post features a conversation among Faith Armstrong, Assistant Professor of Fundamentals of Nursing, Tameka Battle, Associate Professor and Program Director for the Therapeutic Recreation Program, and Michele Piso Manoukian, LaGuardia Center for Teaching and Learning. Professors Armstrong and Battle discuss questions raised in Practitioner to Academic (P2A), a CTL seminar conceived by Director of Nursing, Kathleen Karsten, launched in Fall 2017, and co-facilitated by Edward Goodman (Business and Technology) and Michele Piso Manoukian (CTL). Among the topics explored below are characteristics of professional identities, practitioner/academic distinctions, and the sometimes conflicted transition from professional practice to academic culture. Their conversation also touches on pedagogical practices in which “theory” has always been only one part, and not the whole, of the “professional” classroom. Contents have been edited for length and clarity.

Michele Manoukian: We’ve all known each other a long time—Tameka, you and I connected at a benchmark reading when Burl (Yearwood) was still at LaGuardia as chair of Natural Sciences, and Faith, we had a wonderful encounter many years ago at a CTL college-wide event. I’m grateful to both of you for taking time from your clinical and teaching practices to reflect on our experiences inP2A. For me, the interactions between Health Sciences and Business and Technology faculty created a particular kind of bonding energy; our conversations were so open and unfettered, thoughtful and spontaneous. Can we begin our conversation with your reasons for joining the Practitioner to Academic seminar?

Tameka Battle: Before P2A, I had started the CTL seminar on Gender and Diversity. But I couldn’t continue because I had to teach. I also wanted to join the Carnegie Seminar but, once again, the time was wrong. I came to P2A because I wanted to really look at this thing called academia. What is it? We’re in the space of it, but do we fit in?

Faith Armstrong: Right, do we really understand it? How we define academia intrigued me, and prompted me to apply to the seminar. Honestly, I wanted to figure out the difference between what we do as practitioners and what an “academic” does.

Michele: And did you find one?

Faith: Well, it was such a dynamic workshop. I learned so much. I teach differently because of our discussions, and I think I look at myself in a different light. After the seminar, although I still felt a gap between academic and practitioner cultures, I now see myself as being part of the wider community a little more. I think the energy in our seminar came from our understanding that practitioners appreciate academia as much as other faculty. In the Health Sciences department, we can sometimes feel sidelined, not part of the whole. At least, that’s how I have felt. I think that the P2A bonding energy came from all of us realizing, “Oh, my goodness. There really are gaps between the practitioner, the educator, and the academic.” When you first proposed that question in P2A, I saw myself as a registered nurse, as a practitioner first, then as an educator. I think that’s how most of us in the seminar saw ourselves. Does that make sense?

Tameka: I agree; and I believe that those of us in the Health Sciences would all agree that we have a “professional identity.” For example, while academics may identify as scholars, we identify as practitioners. I see myself as a therapist first. When asked, Kathy (Karsten) said that she identifies first as a nurse, and I always say that a I’m recreation therapist—I’ve spent more years as a therapist than as an educator. In time, perhaps, the way I describe my role will shift, but today that’s what I am.

My professional identity has made me who I am, and many years in the field have made me a particular or different type of educator. When I’m functioning as a therapist, I’m not “teaching.” Rather, I’m practicing skills I’ve acquired through training and practice; I’m licensed and I’m certified. When I’m practicing, I’m in my role as an educator of a patient or client, which is very different from teaching students about the profession and how to assume a professional identity. In the classroom, educating students to be the future nurse or the future therapist—that’s when we are “teaching.”

Michele: It’s interesting that you are distinguishing among three roles: teacher, practitioner, and academic, and that in your world, the “educator” perspective shifts depending on whether you are with students or clients. In the seminar, I’ve learned that as educator-practitioners, you’re “in clinic” as preceptors guiding students in the transfer of classroom learning to a professional setting. As one who has taught film and literature, my only chance to experience transfer of skills is in classroom discussions or essays; I don’t know how students talk about films with friends out in the world. In my mind, there’s less of a gap between your professions and studio arts in which students create and critique their work in the presence of others.

Tameka: Absolutely. In order to make the right decision on the floor, that clinical critical judgment has to kick in. And also, as an educator in the classroom, I really want to prepare my students to be “professional.” I’m telling them the good, the bad, the ugly so that they are well-equipped. I’m not talking about anything scholarly, I’m not talking about pedagogy. I’m talking about, “Tuck in your uniform.” I’m talking about, “Make sure you have proper hand-washing techniques, make sure you speak well, make sure that you always check in with the nurse.” That’s a little bit different from being an academic.

Faith: It’s funny that Tameka points to the ways professionals should dress and speak. Does that awareness change how we think? Our work is shaped by concepts or theories—but it’s more than that. Today I had a performance exam; I walked in and saw students in sneakers, and one came in jeans! I said, “No. I’m not going to tolerate this. Professionalism is about your image and what you represent.” Unfortunately, those students failed the performance exam. To a therapist or a nurse, the professional image is important. When you are in the unit, you have the patient’s life in your hand, and you want the doctors and the patients to look at you in a particular way: you want your appearance to reinforce competence. Also, we must keep in mind that for practitioners, for nurses, our work is a matter of life or death. In a flash, someone can die, so a nurse must think and react quickly.

Michele: One of the first things Kathy Karsten said to me long ago in the Carnegie Seminar was, “Michele, you can interpret literature all you want, but nursing is about life or death.” As far as I know, we don’t have a “code blue” in literary studies, unless it’s the sound of critics hacking your ideas to death.

Practitioner/Academic Distinction

In the seminar, the theme that surfaced again and again was a perceived lack of recognition accorded practitioners by the traditional “academic.” Participants addressed the gap by outlining similarities between these professional identities and informally surveying colleagues’ definitions of “academic.” Faculty explored questions regarding “universal” values and behaviors to which a community of academics commit and display. Or is it simply that belonging to a particular department and its disciplinary values suffices to define membership in academia?

Michele: Tameka, I think it was you who said that you think of an academic as one who has a doctorate and engages in research. At the same time, if I understood correctly, the practitioners also agreed that there’s a mistaken perception that the doctorate is essential proof of expertise in a particular field.

Tameka: I’d like to add that Health Sciences is a very large department. We have these competitive candidacy programs. We advise differently. We admit students differently. So we are separate in a sense because we may not do things in ways familiar to other departments and programs.

Faith: We practitioners need to let academics ‘see’ us. In one of the seminar articles, “The Great Academic-Practitioner Divide: A Tale of Two Paradigms,” the authors claim that academics are dismayed that practitioners don’t read their journals and don’t apply their findings. On the other hand, the authors make the point that the academic’s underlying assumption is that they are the experts, that they know the truth. So practitioners need to change that perception.

Tameka: For the practitioner, there are professional requirements of licensure, clinical, fieldwork, as well as the conferences necessary to stay current. Practitioners seem more structured in their teaching, whereas academics seem more flexible. Is that difference due to different kinds of content?

At the same time, while some academics have deep knowledge embedded in their areas of scholarly writing, there are practitioners who possess similarly deep knowledge within their professional practices. In our P2A discussions, we identified characteristics that practitioners must develop and embody in their roles as academics. These characteristics include a sound disciplinary knowledge base that defines the theoretical and technical skills practitioners must possess and display. Second, practitioners adhere to the discipline’s code of ethics and, as I mentioned earlier, expected professional behavior. Third, practitioners can also conduct research and engage in educational opportunities. As practitioners who are also teachers, it’s imperative to keep abreast of the changes in one’s practice, to use evidence-based practices and research in caring for our clients and teaching our students.

Faith: I’m remembering President Obama’s tweet: “It’s not the red states or the blue states, it’s just the United States.” This is where we are with practitioners and academics. There’s a divide, a gap, and I think it is because we haven’t seen the value in each other. There’s no need for either one to feel isolated or segregated; honestly, it’s not a competition, but it does feel that way, in my opinion. This can be addressed by communicating these valuable distinctions and recognizing that we share a goal: Our students! They are at the center of everything we do.

When I read the article about the academic/practitioner divide, and realized that some practitioners don’t feel that they ‘belong’ or that they are not respected if they haven’t earned the doctorate, I thought about getting published, and how just hearing the word ‘scholarly’ scares some away. But why the divide? I think that unless the institutional culture changes, there will always be a practitioner/academic ‘gap.’ Among practitioners, there’s a feeling of having to prove that we perform as an academic level. Why is that? Is it truly the culture? Or is it the way a practitioner sees herself or himself? If the answer to either of these questions is “Yes,” then we have failed as a community of practitioners/educators, and we risk failing our students.

Both groups have to recognize that coming together is a ‘win-win’ for all involved. I do see similarities between the practitioner and the academic “non-practitioner:” both are hardworking, knowledgeable, motivated, caring, and enthusiastic about their students, about teaching, and about their careers. Both groups of educators want to improve and increase their own professional learning as well.

Michele: Many in our group reflected on concerns or questions about integrating your identity and background as a practitioner with your aspirations as an academic. Could you speak to the challenges of a “dual-identity”?

Tameka: For me, there’s always a question about losing my professional identity as a practitioner: “Does one lose focus on practice when engaging in research that is student-based rather than patient or client-based?” In the seminar, a colleague described developing a “dual identity” as practitioner and academic, and for me that remark was helpful in bridging the gap between being a practitioner and developing as an academic.

Another pressing question is, “How do I find the balance between keeping current in the practice while developing, enhancing, or refining my pedagogy?” My approach is very proactive; I always attempt to stay engaged and active in my own professional development, but the balance between research and scholarly contributions, and being up-to-date in current practices is challenging. I find that limited opportunities for engagement and professional development, plus strict guidelines can make tenure and promotion a very difficult process for some faculty who may not be trained as “academics.”

Michele: What actions or skills can facilitate the transition? Among the practitioner’s skills and strengths, which can aid in the transition to becoming an “academic”?

Tameka: For a practitioner, the transition could be smoothed by training in the terminology that is more familiar to academics. For example, formative/summative assessments, higher-order thinking pedagogy, critical thinking, and reflective thinking are terms that should be shared with a practitioner if we are to create “fluidity” between the practitioners’ and liberal arts classroom environments.

Michele: Do you read the literature in your field? I know that you were recently published.

Faith: I just got published, yes. I’m so excited about that.

Michele: So now you’re an academic! And Tameka you’ve already published.

Tameka: I published an article on high impact practices for first year students and a chapter on cultural competency in a book that our students currently use. It is about long-term care for professional social workers and recreation therapists.

Michele: You’ve mentioned the classroom several times. What was the effect of our seminar conversations on your teaching?

Faith: I learned that pedagogies are diverse and uniquely applied by some of us. For example, I realized that my narrative way of teaching was also effective. And I did not realize that at first. I practice the Socratic method: I have seven or eight students in an inner and outer circle, and everyone must be prepared to respond to my questions. Nobody should come to my class unprepared! If the students in the inner circle can’t respond accurately, then members of the outer circle can jump in and help. This method is very engaging and very supportive, and I’ve really got to listen closely—and so do the students! In our seminar, I recognized that there are ways to demonstrate the effectiveness of this approach, ways to seek evidence for what works and what does not work. That is, how do we know? How do I evaluate my method?

Tameka: Well, for me the benefit of the seminar is that I made the decision to get my doctorate of education in Executive Leadership. We finished P2A in May and I started my doctoral program later that month.

Michele: What happened in the seminar to prompt your decision?

Tameka: I wanted to create an extension of my identity as a professional; I wanted to go a little bit deeper, I wanted to be a scholar involved in research, one who is able to develop new strategies and techniques. I knew that I wanted to do that. And then the second motivation is that I did not want to be excluded at the table. Moving up into leadership and having a seat at the table would be so much easier with a doctorate. There are many opportunities, many doors that open when you have a doctorate. I found I have grown tremendously. And the seminar opened my mind to say, “You know what? I am an academic. I am. I am an academic. Who are you to tell me that I’m not?

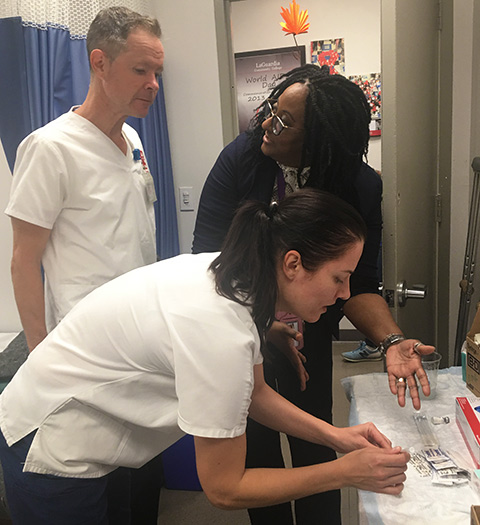

Professors Faith Armstrong and Tameka Battle with MIchele Piso Manoukian of the Center for Teaching and Learning. Photo: Priscilla Stadler

Faith: Yes, this is what I wanted to say: “Okay, see me now.” How do we make ourselves more marketable and how do we become able to grow and develop into different roles, different positions, to become a director or to become whatever we wish? I feel the same as Tameka. Because for me, after the seminar, I actually applied to the Graduate Center, but because of my health I had to take a step back. And I had to complete my publication.

Michele: Did the seminar help you at all with writing?

Faith: Yes, because after the seminar, I said, “You know what? I’m going to do this.”

Tameka: Throughout the whole seminar, Faith, Michele (Mills), and I had conversations about pursuing a doctorate. Our plan was to go into a hotel—we were going to drive to Maryland every weekend. Michele found the school, we were going to split a rental car, get into that hotel room on weekends and work! We had those conversations right here on the fourth floor.

When you think of the hierarchy of college, of institutions, yes, you know your practitioner role is well respected, it is well acknowledged. But when you’re starting to move up, you are assuming a new identity as a scholar, as a researcher, and it only makes you a better scholar and researcher when you have that practice behind you. I can’t tell you anything about nursing. Faith is the scholar, the researcher, the expert. And she will be validated, not only with her RN credentials and every other certification, but also those three letters at the end of her name. Still, completing a doctoral degree is very expensive. A doctorate is not cheap.

Michele: And what about you, Faith?

Faith: I am applying to various schools. I’d like to begin as soon as my daughter Destiny completes her studies in Chinese at Middlebury College in May 2021.

Michele: You know what we need? For faculty-practitioners who are teaching and have family life and are doing doctoral work, we should have a support group, in which you can share what you’re doing. There are so many commonalities even if we’re in different disciplines.

Faith I would love that.

Tameka Right, because whether five, two, or ten years, getting to the end of a doctoral program is a journey.

Michele: Closing words?

Faith: Because of the seminar, we in the health sciences know we have more to offer. And as I’ve said before, I felt seen. Yes, they see us now.